| |

|

|

|

| The story so far... |

|

| You're currently on our features and projects pages, with material ranging from the satirical to the theological. For more features, click here. |

| |

|

|

| Chuckling in the shack |

|

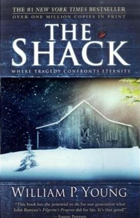

The Shack, a privately-published novel which shot to the top of the New York Times best seller list last year, is selling in its millions. It's become one of those books which you either love or hate. Depicting the Trinity as central characters in a novel is novel enough, but more so when God the Father is an African American woman (and answers to "Papa"), Jesus is an odd job man, and the Holy Spirit (called Sarayu) is slim, female, and Far Eastern in appearance.

The Shack not only deals with the Trinity but also explores the problem of evil, forgiveness, salvation and much more. Liberal Protestants eulogize it; as do open evangelicals of charismatic affiliation, and the emerging church. On the other side, the fundamentalist right and conservative Christians everywhere in America have hailed it as heresy, harmful religion, and corrupting. Andrew Walker, who has lectured on the theology of The Shack at King’s College, London, writes here about his personal view of the book. |

|

I've tried very hard to like The Shack, especially having read some of the nonsense that its traducers have written about it. The claims by some evangelicals, for example, that the book is riddled with heresies are simply wrong. William Young, the author, may be unorthodox, but he is not on the whole heterodox. In my view, the book is more personal catharsis and therapy than Christian doctrine, despite Young's claim that he wrote it as a testament of his religious beliefs for his children and grandchildren.

It must seem churlish of me to criticise a book which hundreds if not thousands of people claim has changed their lives. At the very least, you'd think I could have the decency to acknowledge that The Shack has brought Christian ideas out of the ghetto and into the heart of the secular marketplace. And yet, despite these caveats, I cannot quite shake off my irritation with the book. I'll begin with a small issue that has snowballed in my mind to become a river I cannot cross. The word "cross" brings me to Jesus, and after a snippet of theology and a snatch of scripture, I'll show why I had trouble at The Shack.

We learn about God's love for the world and are able to love him in return by grasping the fact that the incarnation of His Son had serious consequences for Jesus as well as for us. He assumed our flesh so we could be restored to our own good selves, but in taking into his divine person our human nature and sharing it with his own, he became a "man of sorrows and acquainted with grief". For us, restoration entailed reconciliation with God; but for Jesus it entailed death on a Roman gibbet.

This Son of God become Son of Man is at his most poignant and vulnerable in the Garden of Gethsemane when, afraid of dying and in great distress, he calls on his heavenly Father to rescue him from his anticipated torture. His prayer is in a language that touches our hearts; he addresses his Father as "Abba", an Aramaic term of intimacy close to the English word "daddy", but closer still to the French tu. But we also have a foretaste of the vulnerable and frail humanity of Jesus from the shortest verse in the Bible, "Jesus wept". While a holy God demands our obedience and earns our respect, a weeping Jesus commands our love and wins our loyalty.

By contrast, in The Shack, Jesus seems to be done with weeping. We learn in the shortest trope of the novel that "Jesus chuckled". This chuckling Jesus chortles and giggles his way through the book, but it is hard to believe that like the first disciples we would give up our lives and follow him, let alone love him.

Having said that,

we might play with him. Young's Jesus is a down to earth sort of guy, plain as a pikestaff, but nevertheless a man who likes a bit of fun. So too, not to be left out, do the other members of The Trinity: together they are a chorus of chucklers. I don't know why Young decided to let the Holy Trinity chuckle – not least because the word means to titter, or snigger; at best it means suppressed laughter, or laughing so quietly it's barely laughing at all. It seems appropriate, however, that Papa laughs first (on page 98). Jesus first chuckles on page 111, the second to laugh in the sequence of Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Once Jesus starts to chuckle there is no stopping him, and the second time he does it, the chuckling gives way to spasms of mirth. Young is in mimetic biblical verse again a few pages on in the narrative with a simple "Jesus chuckled". A few pages later there is more of the same. Keep turning the pages and the tittering trope is extended when Young adds the filler, "Jesus said with a chuckle".

We are given a little respite from the chuckling Jesus a couple of chapters on, because Papa chuckles for a change. But before the next chapter is out, Jesus is back chuckling for all he's worth. The only member of the godhead who shows some measure of self-control is Sarayu, who only chuckles once.

Chuckling is of course contagious, so it is no surprise that the main character of the book, Mack, who had already expelled an awkward chuckle on discovering that God the Father was in fact a black mom, chuckles along with the laughter of the mysterious Sophia, "not even knowing or caring why". He also has one final chuckle with Jesus about Sophia, whom Mack had initially thought might be the unknown member of the godhead.

It might seem unfair to pick on Young's chuckling God as a problem. Perhaps it is just a case of a restricted vocabulary or a subliminal response to his own chuckling on the way to the bank from the sale of millions of copies of The Shack. But Young's chuckling is more than a linguistic stammer, more than evidence that he is not a wordsmith or literary craftsman: it is also indicative of his tendency to equate laughter with holiness – as natural and good as organic food.

In contrast, the Desert Fathers of the early church period considered laughter to be demonic and evidence of a lack of sobriety, not a characteristic of a loving God. Admittedly, the Fathers were not right about everything and there is no reason to believe that God has no sense of humor. The patristic doctrine of perichoresis (the co-inherence of the persons of the trinity) might seem to lend credence to a shared humour, as the Greek term evokes a sense of perpetual motion, or a never-ending dance routine, but I know of no mention of eternal chuckling.

The trouble for me with the tittering Trinity is best demonstrated by the Jesus character in The Shack. He does not resonate with the Jesus who wept in the Gospel. With St Thomas, I am prepared to call Jesus "Lord and God", but the Jesus of The Shack is another matter. When he is out fishing with Mack, he rebuts his suggestion that he could use his power to catch fish with a surprising reply. "'What would be the fun in that then, eh?' He looked up and grinned." At this point, I am compelled irreverently to call Young's Jesus a "chucklehead" – not a divine title, admittedly, not even a surrogate for a "holy fool", but according to most dictionaries, "a stupid person or a dolt".

I guess my real irritation is with Young himself. I felt it was tawdry to write a sentimental book about a murdered girl (Missy) whose father (Mack) is eventually able to forgive her murderers – and just for good measure is also able to forgive his own father for abandoning him when he was a boy. Sentimentality robs forgiveness of its redemptive shine – "Daddy, I'm so sorry! Daddy, I love you..." – and steps over the line of self-restraint and appropriate show of emotion into silliness. Sentiment, when sugar-coated, rots the teeth of their creative bite and can be malevolent if not malignant.

I am less than sanguine about the invitation at the end of the book for readers to join the Missy Project, as this is clearly intended as a money-raiser: "If you've been touched by the wonder of this book and want to make it available to others..."

Eugene Peterson, who is as good as any scholar with an open Bible, seems less at home in deciphering the merits of a modern text. To think, as he does, that The Shack is so good it will do for our generation what John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress did for his, beggars the imagination. Bunyan's book is an allegory steeped in the language of the King James Bible, Shakespeare and John Milton. The Shack, on the other hand, is a work of the imagination and written in an eclectic style that stumbles from didactic theologizing to counter-culture mysticism and colloquial Americanisms.

It does not have the literary merit or the mainstream appeal to become a literary icon such as Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath or the moral strength and simplicity of Anne Tyler's Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant or Searching for Caleb. It is a significant book, but The Shack is too religiously divisive and intellectually quirky to give it the status of that other American shack, Uncle Tom's Cabin. Maybe it will become a cult book like Pirsig's Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, to be deposited in charity shops and squirreled away in boxes marked, "do not open". |

|

|

|

|

|

| Andrew Walker is Professor of Theology, Culture and Education at King's College, London. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|